Reader Reactions to the Article "A New Analysis of the Audiology Workforce"

Amyn M. Amlani, Ph.D., Victor Bray, Ph.D., Bryan Greenaway, Au.D., Shannon Kim, B.S., Kara Kratzer, Au.D., Timothy C. Steele, Ph.D. and Alexandra Tarvin, Au.D.

In A New Analysis of the Audiology Workforce, Bray & Amlani documented the low growth rate of the audiology profession, compared to other healthcare professions.1 The authors also cautioned readers on the potentially serious professional issues if audiology cannot and does not meet the increasing demand for services to meet the needs of the aging US population. The article stimulated significant interest among Audiology Practices readers, prompting the authors to conduct a follow-up interview to document the reactions and opinions from members of the ADA community in response to the data presented in the article.

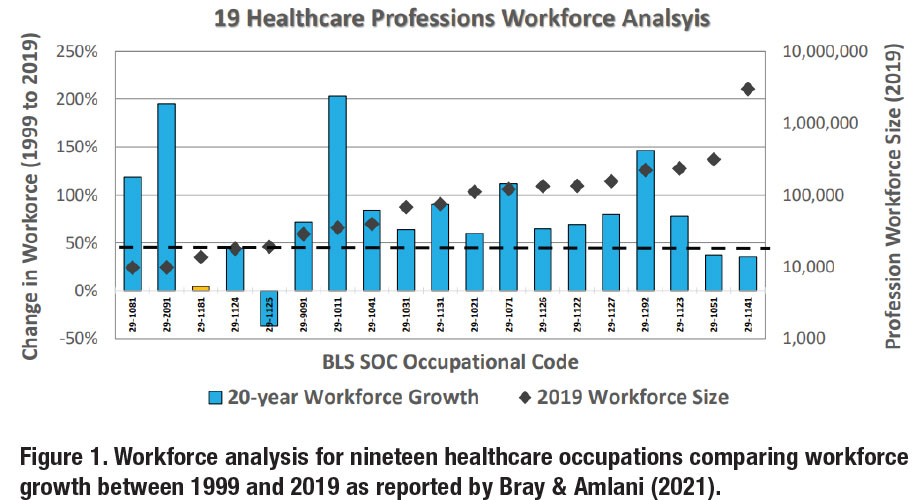

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Thank you for agreeing to provide your feedback and opinions on the information presented in A New Analysis of the Audiology Workforce. Figure 1 of the article consists of a workforce analysis of 19 healthcare occupations, which was originally presented in a poster at the 2021 American Academy of Audiology conference.2 What is your initial reaction to the finding of a 5% workforce growth for Audiology over a 20/21-year span (1999 compared to 2019)? Are you personally concerned about the number of audiologists in the country (too many, just right, too few)?

Dr. Steele: Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani, thank you for asking me to further explore your outstanding and eye-opening article. This type of information is critical to the current and future success of the profession. The very low 5% workforce growth for Audiology over a 20/21-year period, combined with the large growth in the U.S. aging population and with the retirement of baby boomer audiologists, is alarming. I assume we’ve had some challenges with low workforce growth, but I hadn’t expected it to be this low during that time frame. Personally, I’m concerned about the number of Audiologists in the country. We’ve traditionally been very blessed to have several academic institutions near our practice in Kansas and Missouri which have served as a natural pipeline for recruitment but of late it’s become more difficult, and it seems there are more openings than available Audiologists.

Ms. Kim: I am concerned since I believe that our profession is much needed in healthcare. Not only do we treat hearing loss but can provide expertise on implantable devices, tinnitus, BPPV, etc. Tinnitus and BPPV can be incredibly debilitating, and we are able to provide much needed advocacy for these patients.

Dr. Tarvin: My initial reaction to Figure 1’s data is not a surprise. I remember hearing at a national conference years ago the number of audiologists graduating and those retiring were too close for comfort. Giving the small cohort sizes within Au.D. programs, the lack of audiology awareness, and the technology and various sources of industry disruption, I was surprised to see there was any growth at all.

Dr. Greenaway: The growth rate of audiology over the last two decades is concerning. We know we aren’t growing at a rate that is sustainable to serve the hearing needs of the increasing older population in our country. That doesn’t even consider the other populations we can serve through hearing conservation, balance testing, APD testing and treatment, and tinnitus management. Since the introduction of the Au.D. we have labeled ourselves the doctoring professionals who own these areas. However, with our profession’s current growth rate, we’re going to see other professions – some less qualified than we are – slowly eat away at the domains we worked so hard to own.

Dr. Greenaway: The growth rate of audiology over the last two decades is concerning. We know we aren’t growing at a rate that is sustainable to serve the hearing needs of the increasing older population in our country. That doesn’t even consider the other populations we can serve through hearing conservation, balance testing, APD testing and treatment, and tinnitus management. Since the introduction of the Au.D. we have labeled ourselves the doctoring professionals who own these areas. However, with our profession’s current growth rate, we’re going to see other professions – some less qualified than we are – slowly eat away at the domains we worked so hard to own.

It’s also important to look within that statistic to see that we are disproportionately underserving some communities over others, too. The 5% growth number shows a clear issue with access to care, but when patients have to travel hours or take a day off work to get to see an audiologist, we are also exacerbating the affordability issue for our patients.

Dr. Kratzer: This statistic is somewhat concerning to me. As the population of individuals needing hearing healthcare grows and the number of audiology providers decreases, it will be increasingly more difficult for audiologists to keep up. This may lead to an increase in underserved areas, lower quality patient care, as well as workplace burnout.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: We share the concern that many have regarding the lack of long-term growth of the audiology profession. We have been alarmed since we first reported in 2019 that the 1999-2018 change in professional workforce was only 350 persons over a 20-year period at a time when the BLS projected audiologist demand for ten years (2018-2028) was 220 audiologists per year.3

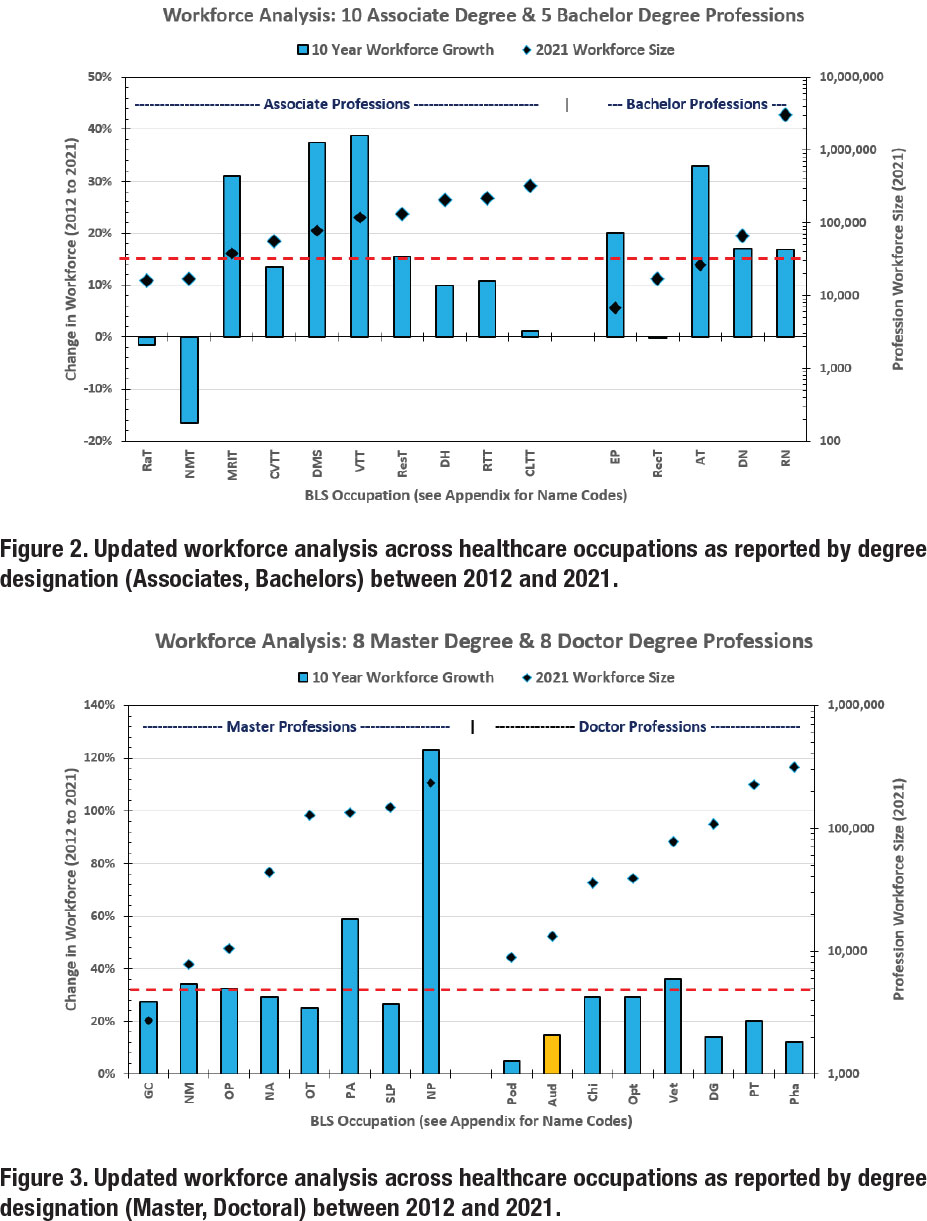

Dr Bray and Dr. Amlani: Figures 2 & 3 show the updated workforce analysis, by degree, 2012-2021 with 10 Associate’s degree professions, 5 Bachelor’s degree professions, 8 Master’s degree professions, and 8 Doctoral degree professions (31 total). Across the four college degree categories, there are different group growth rates: 14% for Associate’s (3 of 10 growing > 20%), 17% for Bachelor’s (2 of 5 growing > 20%), 45% for Master’s (8 of 8 growing > 20%), and 20% (4 of 8 growing > 20%) for Doctoral. The Master’s degree group is the most successful in filling and growing their occupational niche in healthcare.

What is your reaction to this observation, in light of Audiology moving from a Master’s to Doctoral degree profession? Audiology has traditionally been grouped in ‘allied healthcare’ with OT, PT, and SLP. What is your reaction to Audiology’s 10-year lower growth rate (15%) compared to the other professions?

Dr. Steele: I am an advocate for Audiology being a doctoral-level profession, but I can’t help but wonder if the move to a doctoral profession, without the corresponding guaranteed increase in annual compensation, especially early on, may have lowered the growth rate of Audiology. In addition, the added expense for students deciding on careers that require additional education, higher educational costs/student loan debt, and additional years out of the work force may be a barrier for some young people who then decide against a doctoral-level professional like Audiology. If I were a young person evaluating how much schooling is required for an allied health profession while considering average annual compensation and weighing different amounts of student loan debt, I can understand where the doctoral-level entry point for Audiology may be a hurdle too high for some individuals.

Dr. Tarvin: I do not only attribute the difference in growth rate from audiology to the other allied healthcare professions due to the change from Master’s to Doctoral degree. PT also transitioned to a doctoral degree as the terminal clinical degree. In my opinion, the main difference is the lack of understanding of and appropriate referrals to audiology within the medical landscape. OT, PT, and SLP have a broad scope with diverse populations and widely accepted within healthcare. If you were to ask many other healthcare professions what an audiologist does, they would likely stop at hearing and think more about the geriatric population. Audiology has a broad scope that is often unknown or misunderstood for considerations in a patient’s overall treatment plan- from hearing loss, auditory processing, vestibular diagnostics, aural rehabilitation, tinnitus education and management, prevention, and more. Since the other allied healthcare professions have a growing referral need and a generally clearer understanding of their place in the medical landscape (with many job opportunities), it makes sense that an individual would consider those professions worth their effort and a good financial and educational investment.

Dr. Greenaway: For the record, I feel the transition to the Au.D. was a worthwhile endeavor. It was a stepping-stone to greater autonomy and recognition of audiologists as autonomous treating providers. That said, the value of time and earnings potential cannot be overstated for prospective students. When an undergrad is looking at career possibilities and comparing doctoral and master’s options, one can see why a career that requires one-to-two fewer years in school, less student debt, and still offers meaningful work and good earnings outcomes would be more appealing.

Regardless of anyone’s feelings about the transition, the Au.D. is here to stay, and it is our profession’s responsibility to ensure we are doing what we must to attract exceptional students. The cost side of the equation is difficult (we’re not in a position to demand lower tuition costs), but we can increase the value end of the equation. This includes more outreach about the profession and its impacts on health and wellness at the high school, community college, and undergraduate levels. It also means continued investment in advocacy efforts for reimbursement of full scope of practice and appropriate compensation for the services we provide. Legislation like the Medicare Audiologist Access and Services Act is vital in adding to the value of the Au.D.

Regardless of anyone’s feelings about the transition, the Au.D. is here to stay, and it is our profession’s responsibility to ensure we are doing what we must to attract exceptional students. The cost side of the equation is difficult (we’re not in a position to demand lower tuition costs), but we can increase the value end of the equation. This includes more outreach about the profession and its impacts on health and wellness at the high school, community college, and undergraduate levels. It also means continued investment in advocacy efforts for reimbursement of full scope of practice and appropriate compensation for the services we provide. Legislation like the Medicare Audiologist Access and Services Act is vital in adding to the value of the Au.D.

Dr. Kratzer: The information presented in this paper does provide a compelling argument that Master’s level professions appear to have a more steady rate of occupational growth. It appears that moving to a Doctorate level has had an impact on the number of individuals going into the field. I currently serve as an adjunct professor for an undergraduate Communications Disorders program. I routinely have students tell me that they enjoy my class and would be interested in pursuing a career as an audiologist, but the extra years of school are too much. Because of this, they decide to go into speech pathology instead. The question we should consider now is, do the benefits of the doctorate and increased knowledge and skill doctorate level professionals possess, outweigh the negative aspect of restricting growth of the occupation? Another question that should be considered is, how has the return on investment for individuals entering the field grown in response to moving to a doctorate level? In most markets, audiologists have seen an increase in cost and time to obtain a doctorate but not necessarily seen an appropriate increase in salary. For some, the added years and cost of education may not be worth it in the long run.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: We also believe that the doctoral-degree transition has been done, perhaps with unintended consequences, and cannot be undone. The observation that PT has also undergone this transition (and the OT profession is undergoing this transition) while maintaining steady workforce growth does beg the question of what are the lack-ofgrowth issues in audiology? The issue of educational debt may be an important consideration, as our prior work has shown that debt, and debt-to-income ratio is significantly higher for audiology graduates than PT and OT graduates.4

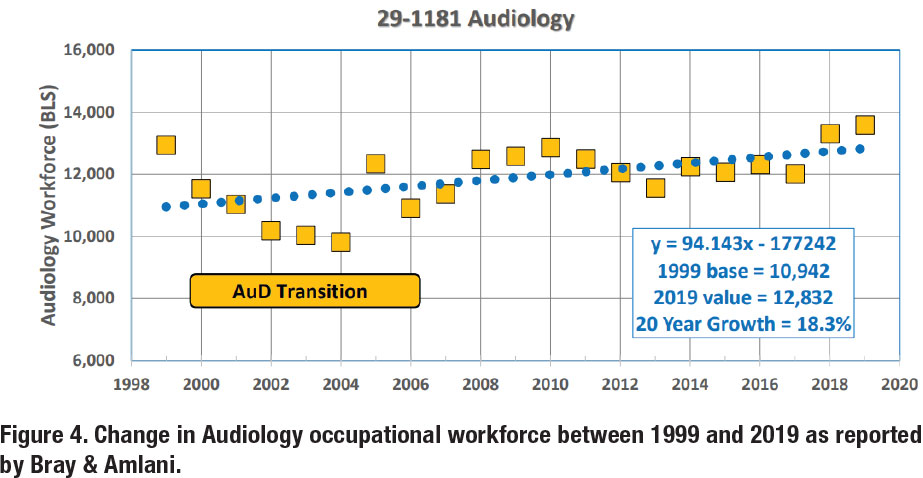

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: As you consider the information presented in Figure 4: Change in Audiology Workforce (1999- 2019), what factor or factors do you attribute the decrease in Audiology BLS workforce from 12,950 in 1999 to 9,810 in 2004?

Dr. Steele: This time frame was during my early career, and I was actually completing a Ph.D. part-time while working as an Audiologist with a Master’s degree. That time of transition in the profession created some uncertainty and this, in turn, may have caused some practicing Audiologists to leave the field. If Audiologists felt they needed a doctorate to remain competitive and/or employable, they may have explored other employment options. Knowing the doctorate would be the eventual required entry degree, I explored applying to Medical School and ultimately decided to proceed with a Ph.D. in Audiology feeling it offered me more flexibility especially since I didn’t have a plethora of Au.D. programs available at that time and wasn’t able to relocate with a young family.

Ms. Kim: I believe there are a variety of factors such as the increase in tuition and the struggle to receive more recognition for our profession. A common complaint I hear is about the price of an audiology education and the return on investment. Students feel that they are paying more to make less money. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median annual pay for an audiologist was $78,950 in 2021. We are a doctoral level degree that specializes in auditory and balance disorders, so a six-figure salary is fair. As for professional recognition, I believe that audiologists deserve more value- hearing health and balance disorder care is much needed in healthcare.

Dr. Tarvin: Regarding Master’s vs. doctoral degree transition, a doctoral degree takes more time, money, and effort to achieve. It is naturally going to have fewer candidates willing or able to engage in this tier of education. In addition, if there were fewer Doctor of Audiology programs available than there were Master’s program, which would have also accounted for the inability for some to acquire their Au.D., even if that was their intention at the time.

Dr. Greenaway: I don’t have the benefit of experience for this time period (the curse of my youth), but a combination of factors likely led to this decline in workforce numbers. While there were larger workforce factors such as a recession in the early 2000s, the high rate of workforce loss during that period seems to be unique to audiology. The transition to the Au.D., no doubt, had an impact on the number of incoming professionals. However, that transition may have only exacerbated other existing issues in the profession. Windmill and Freeman reported in a 2013 paper that the attrition rate of audiologists in the first 10-12 years after graduation was 41% in the years preceding the transition to the entry-level doctorate.5 That may be the more important statistic to look at when having the conversation about what happened in this time period. It may also be important to analyze as we look to the future.

It would also be interesting to see more detailed data on who was leaving the profession during this time. This was also a time of significant technological change, in terms of the hearing aids being fit, the equipment audiologists were using, and the way technology was finding its way into every facet of work and life. It’s possible that also played a role in professionals’ desire to leave a field that was changing rapidly (another possible analogy to our present situation). Again, I don’t discount that the transition to the entry-level degree played a role in this period, but I think you could write a book on the intricacies of this era in audiology.

Dr. Kratzer: More than likely, there are multiple factors that have contributed to this shift. The move to the doctorate, along with an increase in Hearing Instrument Specialists, as well as an increase in those retiring from the profession have likely contributed to this. Another contributing factor may be the small number of Au.D. programs available to students as well as restricting the number of students accepted to these programs. For example, there are currently no Au.D. programs in the state of Georgia. In the past, the Academic Common Market program allowed students in Georgia seeking an Au.D. degree to obtain in-state tuition in certain nearby states. This program has recently ended. Given that Audiologist salaries have not increased much in many areas with the implementation of the doctorate and that students in places like Georgia would not only have to pay tuition for a doctorate level degree, but also have no option but to pay out-of-state tuition costs, some students may be deterred from entering the profession.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: There is no doubt that the Au.D. transition time was chaotic and complicated the student enrollment process with the closure of about one-half of the audiology programs. This was compounded by Master’s degree audiologists who chose to leave the profession rather than stay in the new doctoral-degree environment.

With regard to the important Windmill and Freeman analysis, they concluded a decade ago that “to meet demand, the number of persons entering the field will have to increase by 50% beginning immediately. In addition, the attrition rate will have to be lowered to 20%.” At the time of their analysis (2011 data) the number of graduates entering the workforce was about 600 per year and was offset by a 40% attrition rate. With these considerations, and no changes in workforce growth and attrition patterns, they projected that the number of audiologists would decline over the next 30-year period.

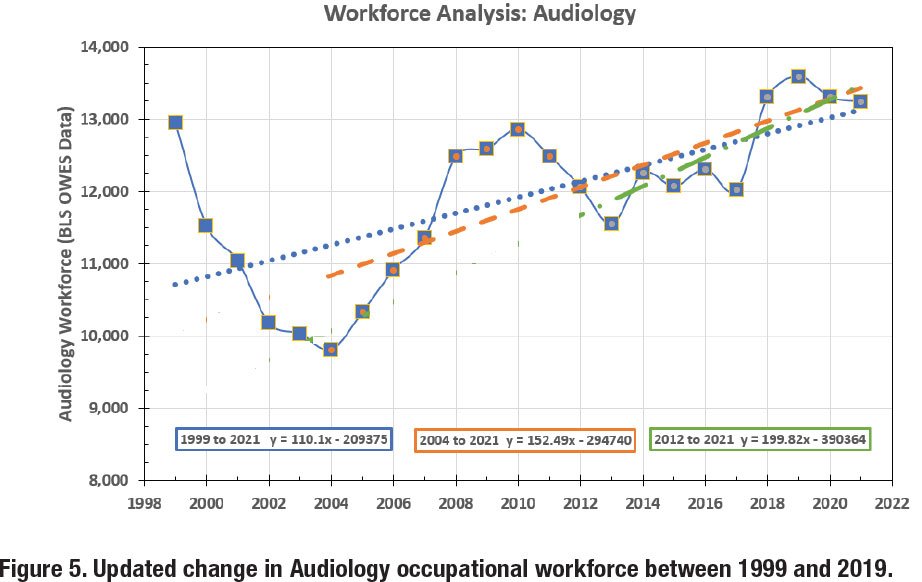

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Figure 5 illustrates the updated Change in Audiology Workforce using three analyses, with the largest rate of growth reported at 200 persons per year from 2012-2021 (1.5% of the BLS workforce size of 13,000). Not reported in the article but known from the CSD Education Survey, is that Au.D. programs are graduating about 760 persons per year (5.8% of the workforce ).6 The profession is theoretically losing about 560 persons per year (4.3% of the workforce). What is your reaction to this, and if you have concern, is it on the number of persons entering the profession, the number of persons exiting the profession, or both?

Dr. Steele: Personally, I feel we need to be experiencing more growth in Audiology and if we are gaining (net) 200 Audiologists per year that seems low relative to the needs of the population and the profession. Within our practice, we’ve seen higher turnover with recently graduated Au.D.s. Of our most recent hired Audiologists over an 8-year period, 40% have left the profession completely to raise their young families full-time while 20% have taken positions outside of private practice. It would be interesting to further explore the 560 persons leaving the workforce each year. I wonder if these attritions are mostly due to retirements or are there other forces at play that we should better understand such as job satisfaction, compensation, work/life balance.

Dr. Tarvin: I had previously heard this statistic early in my career which was not very encouraging. Unfortunately, the data is still discouraging. We have a recruitment problem of encouraging students in high school and early bachelor’s to learn about and consider audiology as a profession. I learned about audiology through sheer luck while exploring undergraduate options in college and came over from neuroscience. While in my undergraduate program, audiology was presented more from the research perspective and speech-language pathology was given much more weight in the coursework mix. When I was in my Au.D. program, several of the professors were recruiting me for a research focus encouraging the Ph.D. route and discounting the clinical application. While clinical and animal research is very valuable, what will be the point if we do not have enough clinical providers to apply the findings to people and their quality of life? Once an audiologist, I hear colleagues leaving or considering leaving the profession for outside options due to some of the logistical challenges of practice. We also have a portion of the 4.3% leaving from natural retirement.

Dr. Greenaway: These numbers are concerning if we want the profession to continue to meet the needs of the US population in hearing, balance, and tinnitus. Necessary workforce growth can result from three options, increasing the number of qualified audiologists who graduate each year, decreasing the attrition rate of practicing audiologists, or a combination of both. Adding more audiologists to the workforce would be great, but we’re seeing a reduction in graduate school applications across healthcare professions and across the country. A cursory look at ASHA’s EdFind website shows that many programs are not meeting their target class sizes. While the profession of audiology has little sway over academic programs, our national and state organizations can do more to promote audiology with potential students. The loss of 560 audiologists a year is also concerning. Without more detailed data on the age of audiologists and why they are leaving the profession, it’s hard to know how modifiable this number is (I suppose we have to let people retire eventually). However, based on the number of articles and interviews I’ve seen over the past year addressing audiologist burnout and stress, my guess is that the profession’s pre-retirement attrition rate is still high. In my view, this is where we can have the most impact as a profession. Our national organizations can and need to play an active role in studying and preventing premature attrition.

Dr. Greenaway: These numbers are concerning if we want the profession to continue to meet the needs of the US population in hearing, balance, and tinnitus. Necessary workforce growth can result from three options, increasing the number of qualified audiologists who graduate each year, decreasing the attrition rate of practicing audiologists, or a combination of both. Adding more audiologists to the workforce would be great, but we’re seeing a reduction in graduate school applications across healthcare professions and across the country. A cursory look at ASHA’s EdFind website shows that many programs are not meeting their target class sizes. While the profession of audiology has little sway over academic programs, our national and state organizations can do more to promote audiology with potential students. The loss of 560 audiologists a year is also concerning. Without more detailed data on the age of audiologists and why they are leaving the profession, it’s hard to know how modifiable this number is (I suppose we have to let people retire eventually). However, based on the number of articles and interviews I’ve seen over the past year addressing audiologist burnout and stress, my guess is that the profession’s pre-retirement attrition rate is still high. In my view, this is where we can have the most impact as a profession. Our national organizations can and need to play an active role in studying and preventing premature attrition.

Dr. Kratzer: I do have concerns that we are not producing enough audiologists to keep up with our country’s hearing healthcare needs. I feel the concern is the number of people entering the profession. Audiology will have to not only continue to advocate for our profession but be creative to fill these gaps and more open to working with other professionals such as hearing instrument specialists (HIS) and audiology assistants to address this need.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Growth in the professional workforce is a dynamic interplay between incoming graduates and exiting retirements and attrition from abandonment of the profession. In a preliminary analysis of graduation rates, as a percentage of the workforce size, we reported an educational pipeline (graduates / workforce) of 4.7% for optometry, 5.0% for physical therapy, 5.8% for audiology, 6.4% for podiatry, and 6.8% for speech language pathology.7

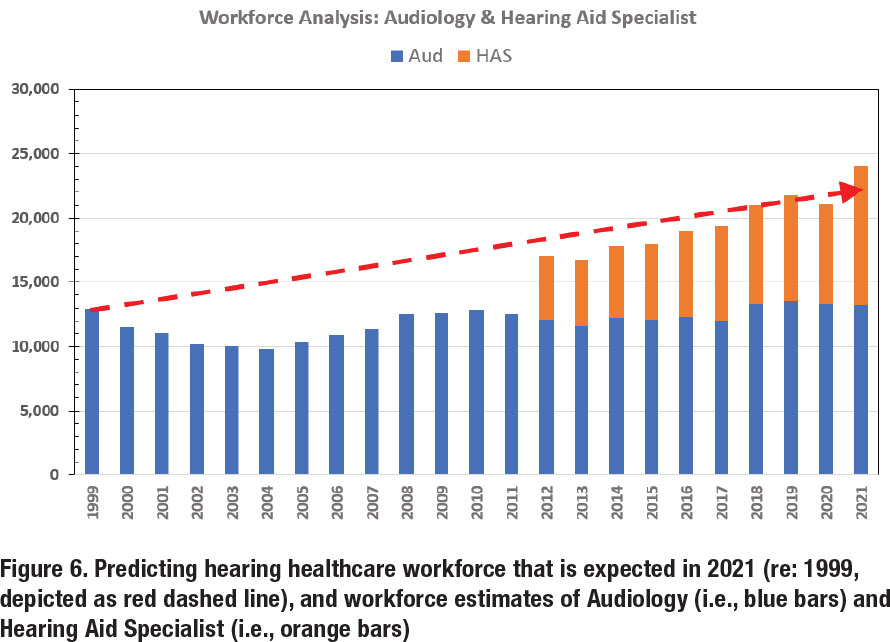

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Considering Figure 6: Projected Possible Workforce in 2021, are you concerned that Audiology may not be meeting the growing needs of the US population? What is your reaction to the more than doubling of the BLS workforce numbers for HAS/HIS over decade (2012-2021)?

Dr. Steele: Absolutely—I can’t believe that our audiology practice would be unique, but it seems harder to find and recruit audiologists which can be even more challenging in rural areas. This year is the first year since 2007 that we haven’t had audiology externship applications with two open externship positions available. We are exploring new ways to deliver services and provide care all while making efforts not to sacrifice quality. The use of audiology assistants/support staff is becoming essential for our business.

I’m not surprised that HAS numbers have doubled, and with the rise in retail options for hearing care it makes sense that these positions have necessitated more hearing instrument specialists. In addition, if we haven’t seen the population needs met by a lack luster growth in the Audiology workforce growth, then it’s an opportunity that HAS have been able to capitalize on especially since the educational/licensure requirements for a HAS isn’t as demanding or costly.

Ms. Kim: I am concerned that Audiology may not meet the growing needs of the US population. I’m also surprised to hear that there will be more than doubling of the BLS workforce numbers for HAS over decade (2012-2021). As for the lack of growth in the audiology workforce, I’ve heard some [potential audiologists/students] explain that if they mainly fit hearing aids, they would rather save money and be a hearing aid dispenser. I understand their viewpoint since student debt is difficult. For me, I went to school to become an audiologist, not a hearing aid dispenser. I went through the education and training in order to do our full scope: amplification, implantable devices, vestibular, tinnitus, etc.

Dr. Tarvin: I am concerned that the number of audiologists is not going to meet the population’s need for proper audiologic care in the near future. If we look at the data regarding how many people in the US have untreated hearing loss, we know that if all of those individuals decided to treat their hearing loss, Audiology and HAS workforce would not be able to meet that need. If everyone that had a balance concern was properly referred needing a diagnostic balance assessment, there would be even larger wait times for vestibular specialists. We are already seeing this within our local ENT clinics. Audiology is not meeting the needs of the US population; however, we are also not seeing the number of patients that we should be given how many individuals need our care that are not being referred for our care.

The more than doubling of the BLS workforce for HAS in the past decade is interesting. I can only answer from my own perspective based on my own observations and it seems that HAS are often recruited. It does not seem to be a profession that someone actively seeks out, but they are recruited by other HAS, audiologists, or businesses to fulfill a clinic’s provider needs. This would then lend to the idea that the growth is fulfilling a need within the hearing healthcare profession at large rather than an individual’s drive to be an HAS. The job outlook is enticing and the financial tradeoff for HAS is good. They can participate in the highest revenue generating scope of audiology practice (hearing aids) without the need for post-secondary education, no student loans, and short-term training.

Dr. Greenaway: I don’t think there is any doubt audiology is not meeting the needs of the US population with its current numbers. As I mentioned before, when we look beyond the needs of Americans with hearing loss, we can see we’re falling short when it comes to meeting the needs of our tinnitus, APD, dizziness, and conservation patients, as well.

Given audiology’s inability to meet the needs of the population, it’s no wonder hearing aid dispensers are growing so rapidly as a profession. They are filling the gaps we are leaving open, and not only in overall numbers, but also in geographic distribution and diversity of providers.

The growth of the profession of hearing aid dispensing could be a benefit to audiology. Hearing aids are requiring less knowledge and skill to fit – just look at what OTCs can do – which means audiologists’ expertise isn’t as valuable in that aspect of our practice. By incorporating dispensers, audiology assistants, and other paraprofessionals into the way we practice, we still ensure our patients are having their needs met while freeing our time for the aspects of our scope that uniquely require our knowledge and skills.

Dr. Kratzer: I do have concerns that we are not producing enough audiologists to keep up with our country’s hearing healthcare needs. The growth in the HAS workforce does not surprise me much. HAS are able to do a portion of the audiologists’ job with zero higher education. From a business perspective if you are interested in only working with hearing devices and not more advanced specialties such as vestibular and cochlear implants, then it might make sense to go straight into the workforce instead of spending many years and a significant sum of money on school. I personally know several audiologists that are retiring and leaving their business to their children who have become HAS.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Marquardt, in 2017, wrote that hearing aid dispensers earn on average $11,000 less per year in real wages than audiologists and that employers may shift employment to hearing aid specialists in situations where the main duty is testing and fitting hearing aids.8 According to the May 2021 BLS reports, the difference in mean wages in the two professions is now around $26,000 ($86k vs. $60k).

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Do you see HAS expansion of scope of practice currently occurring (while audiology scope of practice is not changing), and if so, how does this expansion impact workforce dynamics in hearing healthcare?

Dr. Steele: With a lack of strong growth in the Audiology workforce, it seems natural for a possible HAS expansion of scope to meet the needs and demands of an aging population. I don’t mean to be nonchalant about this but it’s easy to see how or why this might occur. I often reflect on the challenges faced by individuals in rural communities of Kansas and Missouri where I grew up and provide outreach services. There isn’t the luxury of Audiology services in some of these areas and it leaves a void where other hearing care professionals can serve.

Ms. Kim: Professionally and respectfully, I feel that in general, proper training and certification coincides with ethics. As long as someone has proper training and certification for the well-being of a patient and knows when to refer, then it is okay.

Dr. Tarvin: Yes, I see HAS expansion of scope of practice currently happening with intermittent threat throughout the country to continue happening. I do not see the expansion from lack of growth in audiology but rather the internal desire for HAS to be able to do more and bill for more without the need to refer to audiology and “lose the patient” or actually acquire an audiology degree.

Dr. Greenaway: Look at the relationship between optometrists and opticians and you can see the potential for benefit in the growth of dispensers. That being said, I think it’s important to draw lines around training and expertise when it comes to the expansion of dispensers’ scopes of practice. Certain aspects of care require the higher and more standardized level of training that audiologists receive.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: To some degree, there is a continuous expansion in the scope of practice that is being driven by the manufacturers of hearing aids. For example, at one time traditional hearing aids were Class I devices. Class II devices included tinnitus maskers / tinnitus instruments and devices which could be mated with wireless (FM) technology. Class II device functions were generally limited to the scope of practice of audiologists. Today, almost all hearing aids are Class II, with integrated wireless technology via Bluetooth, and often include multi-modal tinnitus features. While tinnitus management may not be within the state-regulated scope of practice for many hearing aid specialists, the universal access to Class II technology enables anyone with a license to fit and dispense hearing aids to now access and utilize the tinnitus management technology provided by industry.

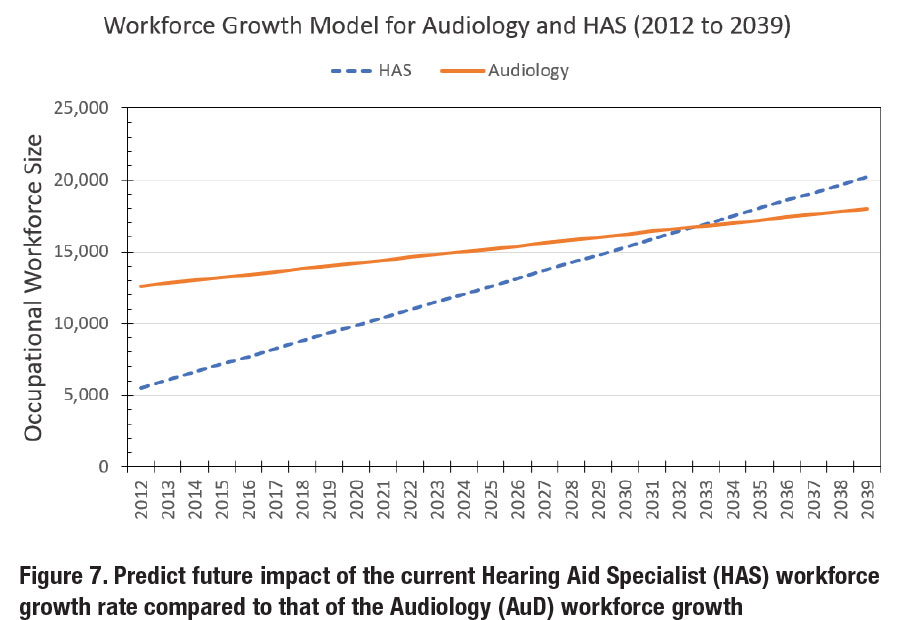

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Considering the projected future impact of HAS as outlined in Figure 7, what is your reaction to the authors’ projection that the HAS workforce becomes larger than the Audiology workforce in ten years? Is this a problem for Audiology or an opportunity, and why do you feel that way?

Dr. Steele: Honestly, I’m surprised about the projections that the HAS workforce could outpace the Audiology workforce in the next 10 years; However, when you think about all the variables playing into the situation we are currently facing, it makes sense. I feel this could be an opportunity for Audiology because it may afford the profession the chance to utilize HAS within our larger professional framework to meet the demands of a growing population in need of Audiological and hearing care. For example, Audiology practices employing HAS that are licensed, well-trained, and practicing under their scope can be assets to the Audiologists and business.

Dr. Tarvin: There are little to no barriers to becoming an HAS. Reason stands that HAS will continue to grow if the opportunity exists and the barriers remain low to make a good living while doing it. This can become a problem for Audiology if Audiology does not continue to diversify and practice its full scope of care. We have to be seen more than a method of receiving hearing aids from the overall healthcare perspective. It can also be an opportunity if Audiology can employ the benefits of HAS within its own care models.

Dr. Greenaway: Given the expanding patient base in the area of amplification and the relatively low barrier of entry for hearing aid dispensing versus audiology, I don’t see any future where dispensers don’t continue to grow their numbers and eventually surpass audiologists in the number of professionals. I think this represents more of an opportunity than a threat for our profession, as long as we are practicing at the top of our scope and we ensure other professions, like hearing aid dispensers, practice within the confines of theirs.

Dr. Kratzer: Although this may be cause for alarm for some individuals, I believe that this can be an opportunity if we let it. I have worked daily with an HAS for the last seven years. I feel that working together makes us both better professionals and allows us to better meet the needs of our patients. Our practice also works closely with HAS in the area who refer patients to us for services they cannot or do not provide. By the same token if we cannot offer a patient something they need that can be provided elsewhere we reach out to our colleagues. By seeking ways to bridge the gap between our two professions and finding ways to support each other and work together I believe we can all have successful and fulfilling careers and serve our patients well.

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Continuing the discussion with respect to Figure 6 and Figure 7 above, is the future of Audiology to transition from the fitting and dispensing hearing aids to managing HAS who do the fitting and dispensing of hearing aids?

Dr. Steele: I believe it will be critical for Audiologists to always understand how to best fit and dispense hearing aids but in examining Figures 6 & 7 while considering the projections, it is realistic that Audiologists could and probably should manage HAS who they work with to meet the demands and address the Audiology workforce shortage. I know there are already existing Audiology practices who utilize this model, and our business has a planned transition to move in this direction in the coming 24-48 months. True for most businesses, it’s most critical to find the right people whether that be an audiologist or HAS.

Ms. Kim: I hope that our profession will have more recognition and be able to utilize our full scope of practice. This may result in doing less fitting and dispensing hearing aids.

Ms. Kim: I hope that our profession will have more recognition and be able to utilize our full scope of practice. This may result in doing less fitting and dispensing hearing aids.

Dr. Tarvin: The idea could be to expand our hearing aid services workforce and outsource portions of our workload onto another profession (HAS) to which they are properly trained to complete the work to our standard of care. There needs to be a large paradigm shift within both professions to go from competing with one another to working in tandem to achieve the ultimate goal of improving the quality of life for people with hearing loss (Au.D. and HAS), auditory processing, and balance disorders (Au.D.).

Dr. Greenaway: There will likely be several avenues in which the audiologist-dispenser relationship will be able to exist. If audiologists are practicing their full scope of practice, having dispensers working in their clinics, taking care of the hearing aid fitting and maintenance component of the practice, would be mutually beneficial. Dispensers would have a constant flow of business from the audiologists’ diagnostic and consultative work and the audiologists will have their time freed up to focus on the more technical and demanding aspects of their practice. There will still be a place for relationships to form between independently practicing dispensers and audiologists, as well. I look to the optometrist-optician relationship as one proven roadmap which our professions could follow.

Dr. Kratzer: Audiologists transitioning away from fitting and dispensing hearing aids themselves in favor of managing HAS to do that work is a real possibility and one of the ways we could work together to address the hearing healthcare needs of our country.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Audiologists who limit their clinical practice to ‘air, bone, speech, and fitting of hearing aids’ are essentially limiting themselves to the technical role of the hearing aid specialist. The preferred future for audiology is to practice at the top of scope of practice and includes expansive clinical opportunities in the complex world of the diagnosis and treatment of hearing aid balance disorders, consistent with a doctoring healthcare profession. Within that high-level role, comes the opportunity to manage audiology clinics who employ audiologists, hearing aid specialists, audiology assistants, and other methods to extend the audiologist’s impact.

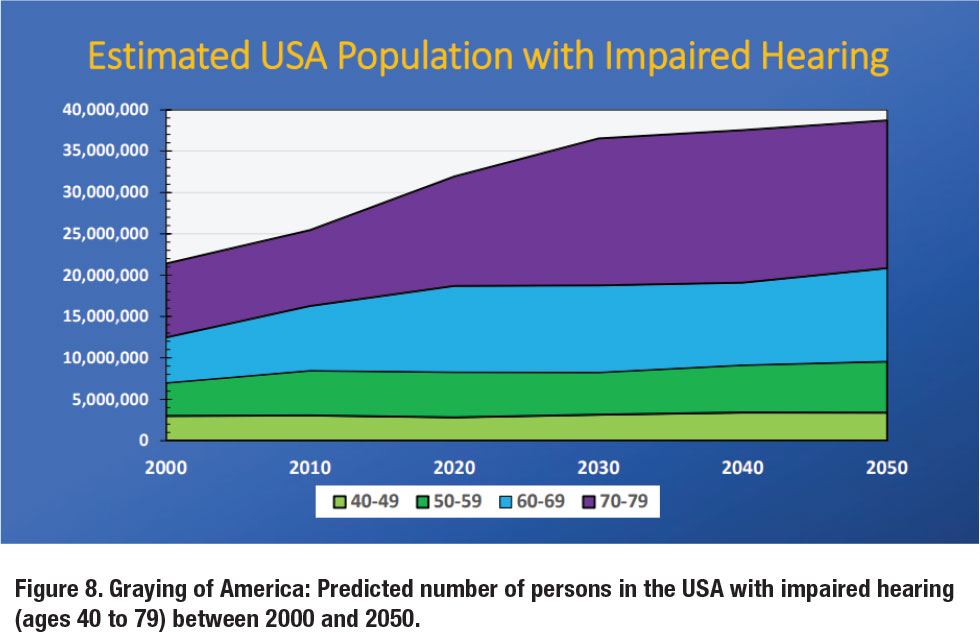

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: According to Figure 8, Projected Graying of America, the estimated (clinician) / (adult_with_ hearing_loss) ratio is changing from 1/1,646 in 2000 to a projected 1/2,283 in 2030, an approximate 38% decline in providers to hearing-impaired adult (age 40 – 79). How do we go about meeting the public health / hearing healthcare needs of this growing segment of the population in the face of diminishing audiology resources?

Dr. Steele: This may be occurring somewhat organically already especially as the data presented in this article support the growth of HAS. In addition, the introduction of OTC into the marketplace will likely open up availability for more complex audiological cases because a younger, more tech savvy, DIY generation can self-manage their early mild hearing loss leaving more availability for an Audiologist to assist an older, more complex patient with co-morbidities. The profession of Audiology may also need to examine other entry level or different level care providers. We could be stakeholders in investigating or creating career opportunities for different educational levels such as associates, bachelor’s or master’s degree specialists with the doctorallevel Audiology degree having the broadest scope capable of supervising other hearing/vestibular/rehab level providers within the larger profession.

Ms. Kim: In general, the public doesn’t realize how important hearing healthcare is and I get many questions about what audiologists do. Advocacy for our profession is personally crucial for me. I served as President of the Student Academy of Doctors of Audiology and lobbied for the Medicare Audiologist Access and Services Act. I discussed the bill for 10 sessions to legislative assistants and policy directors from both House of Representatives and Senate. We can’t let audiology resources diminish- we must use our voices to take a stand for our profession.

Dr. Tarvin: While the amount of people with hearing loss will be significantly increasing, this does not mean that everyone will address their hearing loss issues. With the changes to the delivery model with OTC and DTC hearing aids, some of this increased need will be handled through do-it-yourself options. The standard of care will need to change with more understanding of best practices and utilization of supplementary staffing. The use of audiology assistants, medical assistants, HAS within Au.D. clinics, for example. Audiologists have been completing a lot of the work that has not been required of a doctoral-level profession. The paradigm around how the work is distributed needs to shift to begin to meet the growing needs of the population’s hearing healthcare needs.

Dr. Greenaway: The audiologist-to-patient ratio is daunting, but if our profession does the preparation work it doesn’t have to be a crisis. Audiology has a responsibility to find solutions to meet the nation’s audiologic needs in collaboration with other health professionals and policymakers. Incorporating audiology assistants and dispensers into audiology practices will work to improve the patient load of audiologists. Technological advancements like tele-audiology and over-the-counter hearing devices also have the potential to reduce the strain on audiologists.

Dr. Kratzer: We must get creative and be willing to work together with other professionals. In my clinic we utilize audiology assistants, which reduces the burden of administrative work and also allows us to see more patients in a day without sacrificing quality of care. As discussed earlier, working with HAS both in our clinic and others in our area has allowed us to provide even more care in an underserved population.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: We find it very interesting that our analysis of the number of adults (age 40-79) for the period 2000-2050 is consistent with Figure 1 from Freeman and Windmill (2017) projecting patient demand from 2010- 2040 (image below). They conclude that for audiology to maintain (and defend) its professional scope of practice, while meeting patient demand, audiologists must embrace new technologies and audiology-extenders.9

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Does audiology, as a profession, have the responsibility to establish a workforce target size, based on population and demographic data, and then coordinate a plan of action to meet and maintain the target?

Dr. Steele: If we don’t do it, who will? It seems if Audiology as a profession doesn’t see themselves as stakeholders and more intentionally assert ourselves into our own future, then there will be a natural evolution (that we may not like or that might be too late to turn around) if something more coordinated and thoughtful isn’t initiated. Dr’s Bray and Amlani stated very eloquently that there is a responsibility of the profession to generate a workforce that can service the hearing and audiological needs of the population. The data and projections presented may be an important wake-up call for our professional associations such as ADA to seize the opportunity to steer the course. I’m not convinced that the academic community is best poised to fully make this happen on their own.

Ms. Kim: I believe we have the responsibility to further advocate for our field and better establish ourselves in healthcare. This can be accomplished by getting involved in professional organizations, lobbying at Capitol Hall, making social media content, etc. While I understand we are all busy and have our own personal life situations, doing a small act of advocacy can make a difference. I believe in the future of audiology and our worth in healthcare!

Dr. Tarvin: Audiology as a profession may not have the responsibility to establish a workforce target size but that does not mean it is a bad idea. We are a generally small profession with a large responsibility for helping people rehabilitate one of their body senses. The medical community in total has a responsibility to understand more about audiology’s place in the medical landscape. We should be more leveraged as a peripheral health profession and be a part of healthcare teams. The greater the understanding of our care and services, the more resources we may be afforded. If our ability to bill insurance for the services we provide within our scope increase, receive proper reimbursement for those services, receive proper classification for our profession and skills within the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and other victories are achieved, the interest in our profession may go up. Without an increase in respect and awareness and fundamental changes to systems (including education in medical schools regarding audiology) I do not see a realistic increase in our workforce. Since we are a small profession, we can work together to create change but others have to be willing to hear what we have to say (pun intended).

Dr. Tarvin: Audiology as a profession may not have the responsibility to establish a workforce target size but that does not mean it is a bad idea. We are a generally small profession with a large responsibility for helping people rehabilitate one of their body senses. The medical community in total has a responsibility to understand more about audiology’s place in the medical landscape. We should be more leveraged as a peripheral health profession and be a part of healthcare teams. The greater the understanding of our care and services, the more resources we may be afforded. If our ability to bill insurance for the services we provide within our scope increase, receive proper reimbursement for those services, receive proper classification for our profession and skills within the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and other victories are achieved, the interest in our profession may go up. Without an increase in respect and awareness and fundamental changes to systems (including education in medical schools regarding audiology) I do not see a realistic increase in our workforce. Since we are a small profession, we can work together to create change but others have to be willing to hear what we have to say (pun intended).

Dr. Greenaway: Audiology does need to pay more attention to geographic and demographic holes in care, though. We have to be better at recruiting audiologists who reflect the diversity in background and experience of our patients. We also need to make it more enticing for audiologists to work in rural and other underserved areas. Again, tele-audiology and audiology assistants can help fill in the gap for underserved areas, but they will never take the place of having an actual audiologist in those communities. In Oregon, we are beginning to look at state grants and loan forgiveness programs for medical providers in rural and underserved areas and exploring how audiology can be added as eligible providers. State and regional audiology associations are going to be vital in this kind of change.

Dr. Kratzer: While there will always be some factors outside our control, I do believe we have a responsibility to do the best we can for our patients. Being open to adapting our service models and working with other professionals will go a long way in bridging this gap. Additionally, advocating for our profession and promoting it to undergraduate programs may help in encouraging students to pursue a career in audiology. Lastly, addressing the pay gap between the cost of pursuing a doctorate and the average pay of an audiologist may also encourage more professionals to enter the field.

Comment from Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Our work, and that of others, documents an anemic pattern of workforce growth in the 21st century, to which we previously wrote “these comparative numbers indicate that Audiology, as a profession, is showing a failure to thrive.”10 The fundamental issue is: are we, as a profession, going to respond?

Dr. Bray and Dr. Amlani: Thank you to our illustrious panel for providing additional insight into challenges and opportunities presented by the audiology workforce data and recommendations for the profession of audiology and audiologists to address the growing audiologic health care needs of the population, given the projected shortage of audiologists. ■

References

- Bray, V. & Amlani, A. (2022). Audiology Workforce: A New Analysis of the Audiology Workforce, Benchmarked to Other Healthcare Professions. Audiology Practices, 14(4),42-58.

- Bray, V. & Amlani, A. (2021, April 14-16). Historical Trends in US Audiology Workforce, Benchmarked to Other Healthcare Professions [Poster Session]. American Academy of Audiology, Virtual Conference, USA.

- Bray, V. & Amlani, A (2019, November 16). A Critical Review of Audiology Employment and Provision of Hearing Healthcare Services [Conference Session]. Academy of Doctors of Audiology Conference, National Harbor, MD, USA.

- Amlani, A. & Bray, V. (2022, 30 March – 02 April). Analysis of the AuD Educational Debt-to-Income Ratio, Benchmarked to Other Healthcare Professions [Poster Session]. American Academy of Audiology Conference, St. Louis, MO, USA.

- Windmill IM, Freeman BA. (2013). Demand for audiology services: 30-yr projections and impact on academic programs. J Am Acad Audiol, ;24(5):407-416. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.24.5.7. PMID: 23739060.

- https://www.asha.org/siteassets/uploadedfiles/communication-sciences-and-disorders-education-trend-data.pdf

- Bray, V. & Amlani, A. (2022, November 18). Analysis of Audiology and the (4-year) AuD Degree [Conference Presentation]. American Speech Language Hearing Association Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA.

- Marquardt, K. (2017, July 18). Supply and Demand of Audiologists in the US, part 3. Hearing Health and Technology Matters (HTTM).

- Freeman, B & Windmill. (2017, February 7). Demand an Audiologist, but will there be one available? Hearing Health and Technology Matters (HTTM).

- (See 2).

Victor Bray, MSC, PhD, FNAP is an associate professor at Salus University Osborne College of Audiology in Elkins Park, PA. He can be reached at

Amyn Amlani, PhD, FNAP is President of Otolithic, LLC, with its global headquarters in Frisco, TX. He can be reached at

Bryan Greenaway, Au.D. is an assistant professor at Pacific University’s School of Audiology in Hillsboro, Oregon. Dr. Greenaway serves as the President of the Oregon Academy of Audiology.

Shannon Kim is an audiology extern at the Cleveland Clinic and a student at A.T. Still University. During her 2022 term as national SADA President, Ms. Kim represented thousands of student voices by advocating for the Medicare Audiologist Access and Services Act.

Kara Kratzer, Au.D. is a clinical audiologist at Southeast Kentucky Audiology in Corbin, Kentucky. Dr. Kratzer is a member of the Board of Directors of the Kentucky Academy of Audiology.

Alexandra Tarvin, Au.D. is the founder of Elevate Audiology Hearing and Tinnitus Center in Easley, South Carolina. Dr. Tarvin is a Past President of the South Carolina Academy of Audiology.

Timothy C. Steele, Ph.D. is President and CEO of Associated Audiologists, Inc. an Audiology private with eight clinics and 36 employees in Northeastern Kansas and Northwest Missouri area.