The Work of Leaders: Vision, Alignment and Execution

Julie Straw

Across from our Minneapolis office is a restaurant called The Super Moon Buffet. The word “super,” however, is an almost coquettish understatement. It is massive. The theme is technically Chinese, but the ambition here goes way beyond what any single country could dream up. They’ve got sushi, French fries, ham, fresh fruit, roast duck, dim sum, apple pie, barbecued spareribs, stir-fried frog legs, baby octopus, pork chitterlings. It’s overwhelming. Each person has to come to terms with the Super Moon in his or her own way. Some people avoid paralysis by simply diving into the first dish that strikes them. Some rely on advanced mapping software. When we take out-of-towners there for lunch, they walk out the door and ask, “What just happened?” This experience is not completely unlike sorting through the selection of leadership books on Amazon. It is massive, but not necessarily in a bad way. Just like the buffet, of course, there’s some junk in there. (What is a chitterling anyway?) But mostly there are really brilliant, helpful, and practical insights. People who’ve spent a lifetime leading or studying leadership are willing to share their wisdom with the rest of us. The problem, however, is organizing and making sense out of all this information. To say the least, it’s overwhelming. We work for a company that’s in the learning business. It’s our job to make sure that people not only have access to information, but that they can actually absorb it. So, we had a major task ahead of us when we set out to develop our own leadership training program more than a decade ago—make this wealth of leadership insight accessible to all kinds of people in all kinds of organizations. The key word here is “accessible.”

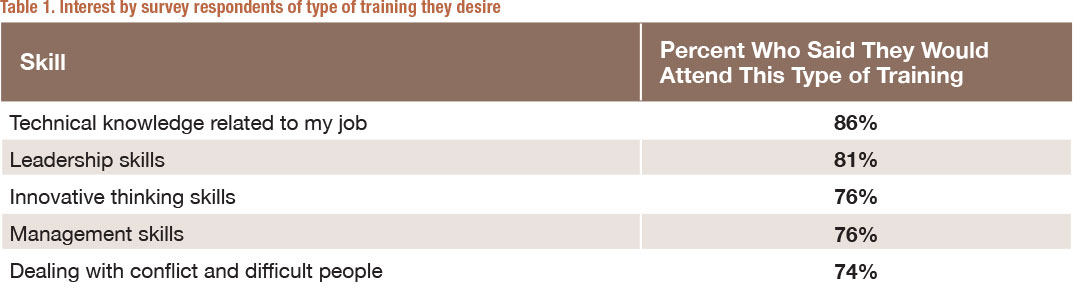

Now, we know that people want to access this information, and we’re not just talking about the people at the top. We asked more than 5,900 training participants in which skill areas they would voluntarily spend their time attending training. Table 1 shows the top five results. Not surprisingly, people are most willing to attend training that has direct, concrete applications in their world— “technical knowledge related to my job.” It’s good to know how to do your job. But look at what’s a close second with 81 percent: “Leadership skills.” In fact, when we asked people what training would greatly increase their effectiveness knowledge related to my job the number one answer, by far, was also leadership skills. More than half of the workers in our sample said they’ve read one or more leadership books in the past two years. Managers are more interested in attending leadership training than management training. People feel that there’s a lot to learn—and there is. But again, this information has to be accessible if it’s going to make a real difference in anyone’s work. So that’s what we set out to do—make leadership accessible. In essence, our goal was to study all of the most respected thinking and research on leadership, focusing on common themes and major breakthroughs, and follow up with our own research, gaining clarification on the most promising ideas.

The first stage, our literature review, was, frankly, exhausting. Over the course of about five years, we worked with a team of people finding the best thinking on leadership. Now, it turns out that finding the best thinking also means reading a lot of the less-than-best thinking. But that’s okay; nobody got hurt. We also realized that if we wanted to come up with a truly comprehensive view of leadership, we would have to include writers from a broad range of perspectives: Contemporary authors like Marcus Buckingham and Seth Godin and classic authors like Peter Drucker and Warren Bennis. Authors who come from an academic background like Peter Senge and Daniel Goleman and authors who come from a consulting background like Liz Wiseman and Patrick Lencioni. Leaders who have thrived in the non-profit sector like Frances Hesselbein and Gloria Duffy and leaders who have thrived in the corporate world like Larry Bossidy and Harry Jensen Kraemer, Jr. Authors who come from a highly philosophical perspective like John Maxwell and Max De Pree and authors who come from a highly research-based perspective like Jim Collins and Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner The goal was to pull out a simple structure that still captured the richness within all of this thinking. That is, what are the biggest, most important ideas? Then we moved on to verify and build on what we had learned. We wanted clarification on these big, important ideas. How do they hold up under scrutiny? How do they apply to the work leaders do on a daily basis? As it turns out, we were in a highly enviable position to take on this sort of inquiry. We work for an organization that, among other things, helps hundreds of thousands of managers and leaders every year understand the relationship between their personalities and their work. We have as many as 3,500 people a day completing one of our online assessments, many of whom are gracious enough to help us out with our leadership research. As a result, we can study the attitudes and behaviors of literally thousands of leaders every week. Collecting data of this magnitude usually takes months. Extensive resources are needed. Undergraduate psychology majors can be locked in rooms for weeks until they tabulate piles of surveys. Our setup, on the other hand, gave us the opportunity to quickly test hypotheses, look at the results, then test some more. We could pit grand theories and conventional wisdom against the real work that leaders do, every day. Ultimately, the VAE model was created in ten stages of development. You can read in more depth about this process in our book, The Work of Leaders. And so, we’re happy to say that, throughout that book, we are able to provide results from dozens of studies that we have conducted over the past ten years with hundreds of thousands of participants. Given all this information, however, we were sure not to lose sight of our end goal—to create a framework of leadership that was accessible and actionable for everyone—not just the CEOs. We wanted to take the mystery out of leadership and spell out a leader’s responsibilities as clearly as possible.

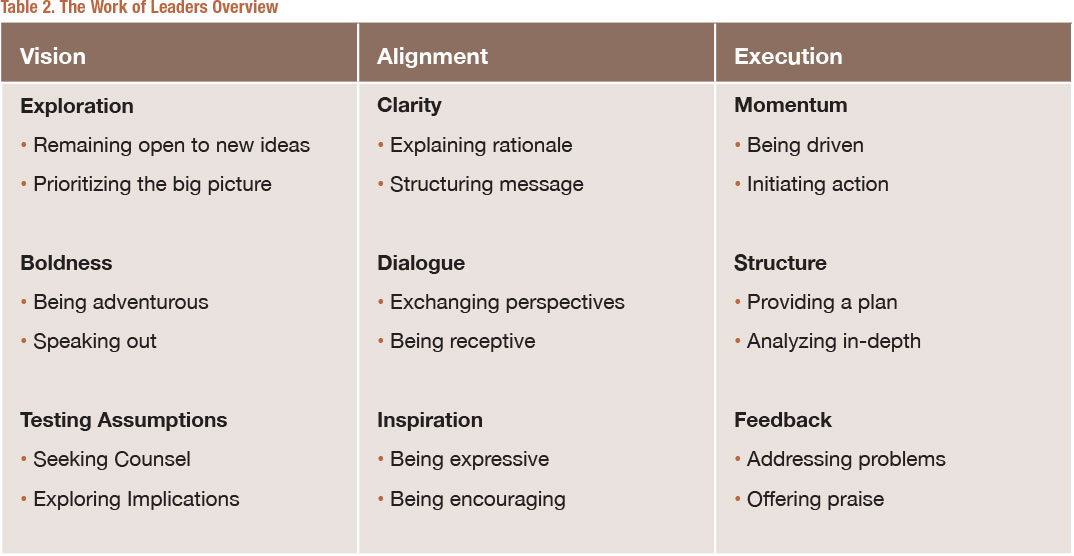

The result was a leadership model of Vision, Alignment, and Execution—what we call the VAE model. The VAE Model suggests leaders have three fundamental responsibilities: They craft a vision, they build alignment, and they champion execution. Of course, there’s a lot of skill that goes into each element of the VAE Model.

First, it helps to have some quick definitions of each of the three elements.

- Crafting a Vision: imagining an improved future state that the group will make a reality through its work

- Building Alignment: getting to the point were everyone in the group understands and is committed to the direction

- Championing Execution: ensuring that the conditions are present for the imagined future to be turned into a reality.

All three are part of a dynamic, fluid process. While there is a loose order implied in the VAE model, the actual Work of Leaders is not strictly sequential. Although it makes sense to craft a vision before aligning around it and executing on it, leaders are continually revisiting and reshaping their visions of the future. Likewise, we need to have buy-in before any major push toward execution, but maintaining alignment is an ongoing process. There is, obviously, a great deal of complexity in doing the work of a leader, but the true value of this model is that it lays out a manageable, realistic framework to guide the process. The goal is to provide straightforward explanations of where you might choose to target your personal development efforts.

Now, let’s look at some cornerstone principles of leadership, according to our model.

- The VAE model approaches leadership as a one-to-many relationship, as opposed to the one-to-one relationship of management.

- The Work of Leaders is done by leaders at all levels. Whether you are a senior executive or a leader on the front line, the process of leadership follows the same path.

- The Work of Leaders is a collaborative process, but the journey to becoming an effective leader is a personal one. Some of the skills and best practices outlined here may come to you more easily than others.

Last, let’s examine some of the key behaviors associated with each of the three elements of the VAE Model. They are outlined in Table 2.

You certainly don’t need to be a master in all of these areas: vision, alignment and execution, but our research suggests that to be an effective leader some level of skill in all three drivers is a must. In the end, leadership development, like any personal development, is about energy. Where do you put your energy and how much do you put in?

To learn more about the VAE Model and how to bring it to life in your practice, please see The Work of Leaders: How Vision, Alignment, and Execution Will Change the Way You Lead by Julie Straw, Barry Davis, Mark Scullard, and Susie Kukkonen. Wiley Press. ■

Julie Straw is the President of Northern Lights Training Solutions, LLC, in Minneapolis, MN.