Audiology Assistants and State Regulation: What's Best for Audiology?

Carolyn Smaka, Au.D.

Audiology Assistants: Key Strategy for Practices to Thrive

Disruption to audiology practices is coming from many sources today—inflation, the labor shortage, industry mergers and acquisitions, competition from retail and big box stores, declining reimbursement rates from third-party payers, and over-the-counter hearing aids on the near horizon, to name a few. Audiology thought leaders have recommended several strategies for audiologists to compete and thrive in these changing times. These include practicing to the full scope of practice as allowed by state law, unbundling the cost of services from devices, offering concierge level services, providing ancillary, related services like cognitive screenings, and increasing the use of audiology assistants and support personnel (e.g., Larkin et al., 2016; Cavitt, 2018; Taylor, 2016; Kingham, 2022). Research indicates that the use of audiology assistants is indeed increasing (Wince et al., 2022). Audiology assistants are intended to improve the accessibility, productivity, and profitability of audiology practices. By taking on administrative and routine tasks, audiology assistants enable audiologists to focus on activities that require complex diagnostic and treatment expertise. Additionally, research suggests that re-allocating administrative tasks to audiology assistants may have a positive outcome on workplace stress for audiologists (Emanuel, 2022).

Dr. Kristin Davis, audiologist and owner of Davis Audiology, a private practice with three locations in South Carolina, reports that audiology assistants allow her practice to provide excellent patient care and support, at a level that would not be possible without the use of assistants. Davis states, “In our practice, audiology assistants significantly improve access to care for patients by providing same day/next day availability for device clean and checks, device repair processing and check in/out, and Bluetooth troubleshooting, among other services.”

More autonomy for audiologists to hire, train and use audiology assistants supports our professional future.

Regulation is Increasing

In 2014, Liebe reported that “few states presently regulate or define the scope of practice for audiology support personnel”. In 2018, Karzon et al. noted a trend toward more regulation for audiology assistants. Since that time, new initiatives to regulate audiology assistants have emerged. It seemed like a good time to review what’s happening overall to help empower audiologists with information so that they can lead and support initiatives that will best serve their practices, their patients, and consumers in their state. Inconsistent Laws and Rules Across States

If you practice or have practiced in more than one state, you are familiar with the wide variability in audiology state laws and rules. There is even more inconsistency in regulation when it comes to audiology assistants. The following summary of state regulations is provided as an overview; it was compiled from information from state licensing agencies and is subject to change. As always, consult your state directly as well as your attorney to guide any decisions for your practice.

LICENSURE

The purpose of licensure is to protect consumers and ensure quality, although research on occupational licensure indicates that licensure requirements do not always align with public health or safety concerns (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2017).

Today, six states (OH, OK, MA, MD, MT, TX) and the District of Columbia require licensure for audiology assistants. Montana has not yet started issuing licenses for assistants; it is anticipated to start accepting applications in Fall 2022. Maryland’s law indicates an October 1, 2022, start date for assistant licensure.

The minimum educational requirements for licensure as an audiology assistant varies by state, ranging from a high school diploma to a bachelor’s degree in speech-language pathology or audiology plus additional observation and/or training. Texas requires Certification from the Council for Accreditation of Occupational Hearing Conservation (CAOHC) or a bachelor’s degree in communicative sciences and disorders; 25 hours of on-the-job training is also required for all Texas applicants.

Fees, training, amount of supervision, permitted and prohibited duties, duration of licensure, renewal requirements including continuing education requirements, maximum number of allowable assistants per supervisors, and other parameters also vary among these states.

If public health and safety is the goal of licensure, the question is how these disparate licensure requirements - for the same profession - can all purport to meet that goal.

REGISTRATION

Today, 11 states require registration for audiology assistants (AL, CA, DE, GA, MO, MS, NC, NE, RI, WV, WY).

Registration requirements also vary widely. For example, Rhode Island refers to ‘audiometric aides’ and requires applicants to have a high school diploma and on-the-job training, while applicants in Alabama must possess a bachelor’s degree in communication sciences or a related field.

Although registration may be intended or perceived as a looser regulatory path than licensure, registration requirements can be rigorous. In Nebraska, for example, the minimum educational requirement for registering as an assistant is a bachelor’s degree or an associate degree from an accredited training program in communication disorders or the equivalent. The regulations further stipulate specific requirements for 70 hours of the applicant’s coursework (or equivalent training), and additional training requirements for those who will provide aural rehabilitation.

Terminology

The term ‘audiology assistant’ is consistent with the terminology used by the Academy of Doctors of Audiology (ADA), the American Academy of Audiology (AAA), and the American Speech-Language- Hearing Association (ASHA) to refer to audiology support personnel. States’ laws and rules include other terms (in addition to ‘audiology assistant’): audiology aides; audiologist assistant; audiometric technician; audiometric aides. These terms may or may not be equivalent and are noted when referenced.

OTHER REGULATION OR MENTION: IT’S COMPLICATED

Fourteen states do not require licensure or registration for audiology assistants but have some type of state guidance in place for use of assistants via their laws, rules and/or practice acts (AR, CT, FL, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, LA, ME, PA, UT, VA, WI).

These regulations vary considerably from state to state. Some regulations are more detailed, for example, Iowa has two categories of audiology assistants, Audiology Assistant I and II, which have their own training and supervision requirements. Florida requires a state certification for assistants.

Other states have more general guidelines. For example, the Connecticut Audiology Practice Act stipulates supervision requirements for assistants (i.e., direct and on-site from a licensed audiologist) as well as prohibited activities for assistants. This brief section in the CT Audiology Practice Act ensures that licensed audiologists have the autonomy and flexibility to use assistants in their practices to improve productivity and profitability, and at the same time provides common-sense guidelines to ensure patient safety.

Arkansas and Maine have rules that simply state that audiologists may delegate certain tasks under supervision.

Two states do not appear to allow audiology assistants. New York’s practice guidelines for support personnel indicate that the terms “audiology assistants” and “audiology aides” may not be used although certain support tasks that do not require a professional license may be delegated to unlicensed personnel. New Mexico’s Board has a letter posted on its website indicating that audiologist assistants are not allowed per the state statute.

NO MENTION OF ASSISTANTS

The remaining 17 states have no mention of audiology assistants in their laws or rules. In these cases, it does not mean audiology assistants are ‘allowed by omission.’ When state laws and rules are lacking or unclear, audiologists should inquire in writing with the state licensing entity and consult their own legal counsel to determine whether/how to use assistants.

Best Practice in Regulation: Less May Be More

Head spinning? Given the hodgepodge of existing regulations around audiology assistants, it is hard to discern what is actually best practice, especially when evidence that it improves the quality or safety of audiology services is lacking.

Regarding licensure, there is little evidence that it improves service quality, health, or safety (Kleiner, 2017), particularly for occupations like audiology assistants where the risk to public health and safety is low. The argument for licensure is strongest when low-quality practitioners can inflict serious harm (e.g., pilots, physicians, etc.), or when it is difficult for consumers to select a quality provider (White House Report, 2015), neither of which applies to audiology assistants. The negative impacts of licensure are also well documented (see NCSL, 2017; Kleiner, 2017) and may include:

- Reduced employment, smaller application pool. Imposing requirements such as additional training and education, fees, exams, and paperwork, reduces employment in licensed occupations.

- Higher costs to businesses.

- Increased prices of goods and services for consumers.

- Reduced competition and market innovation.

- Reduced geographic mobility for workers due to inconsistent licensure requirements across states. This impacts military families and others.

The licensure of audiology assistants comes with additional potential risks for the audiology profession: Licensure may be a path to autonomy and independent practice; licensure may be a means of becoming credentialed with insurance and third-party payers; and licensure plus an established scope of practice may be the first step toward expanding that scope of practice.

A best practices approach to occupational licensing and regulation should strike a balance between benefits and costs (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2017). Revising or removing regulations is typically much more difficult than enacting them. Therefore, when considering new regulations, it is important to conduct comprehensive cost-benefit analyses and to avoid unnecessary and overly restrictive requirements.

Professional Associations: Positions and Initiatives

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF AUDIOLOGY POSITION STATEMENT

In 2021, the American Academy of Audiology (AAA) issued a position paper on audiology assistants. The AAA position statement does not support licensure for audiology assistants. The statement indicates that there is no need for state licensing of audiology assistants since assistants should only work under the supervision of a state-licensed audiologist, who is ethically and legally responsible for all services provided, for patient safety, as well as for the assistant’s training and ongoing competency.

AMERICAN SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION ASSISTANT CERTIFICATION

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) recently introduced the ASHA Assistants Certification Program to certify Audiology Assistants (AA) and Speech-Language Pathology Assistants (SLPA). According to the January 2022 ASHA Board of Directors Meeting Report, there are currently 24 Certified Audiology Assistants (C-AAs). Five states have proposed or made changes to their SLPA regulations to align with or recognize the ASHA certification, and several other states are considering similar changes. Whether or not similar changes to audiology state regulations will be introduced is not noted in the report. The report states that the ASHA staff working group will recommend future initiatives, programs, and priorities in this area.

ACADEMY OF DOCTORS OF AUDIOLOGY POSITION STATEMENT

The Academy of Doctors of Audiology (ADA) position statement (ADA, 2021) defines audiology assistants as unlicensed, entry-level support personnel, trained by audiologists to carry out routine tasks so audiologists can focus on complex clinical diagnostic and treatment procedures. Per this definition, the audiology assistant’s role is consistent with the assistant’s role in other clinical doctoring professions, e.g., medical assistant, optometric assistant, chiropractic assistant, dental assistant, veterinary assistant, and occupational and physical therapy aides. The ADA statement provides an extensive review of research on occupational licensing and concludes that the risks outweigh the benefits when it comes to licensure for audiology assistants.

ADA Model State Licensure Law for Audiology

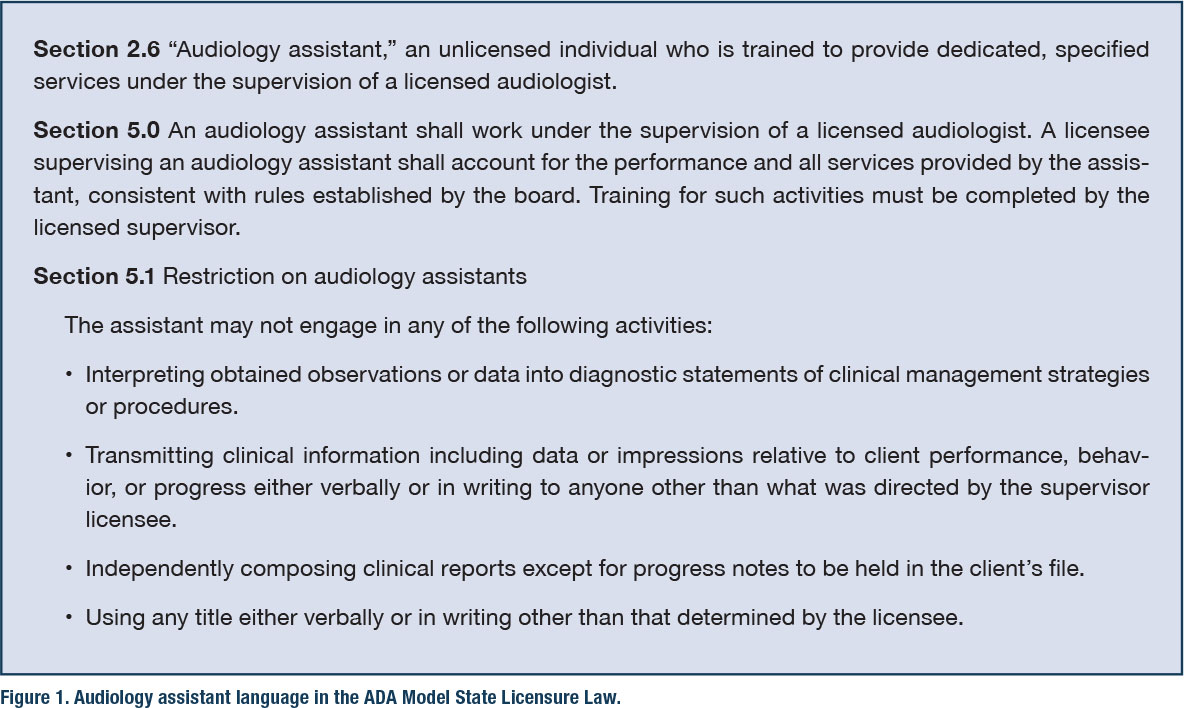

In 2005, the ADA developed a Model State Licensure Law that suggests best practices in audiology state regulation. Recently, the ADA Model Licensure Committee reviewed the Model State Licensure Law to ensure that the language aligns with changes in audiology practice and the regulatory environment. Figure 1 includes those sections of the ADA Model State Licensure Law that reference audiology assistants. It may serve as guidance for audiologists looking to enact or change state regulations for audiology assistants.

Summary

Hamil and Andrews estimated the number of audiology assistants in the U.S. to be 4,250 in 2017, and a recent study indicated that the employment of audiology assistants is increasing (Wince et al., 2022). There currently exists a patchwork of different requirements across states, and the trend is toward more regulation for audiology assistants.

When considering new regulations for audiology assistants, due diligence is required to look at both benefits and risks. Although revising and removing regulations is typically more difficult than enacting them, there are means to do so if existing regulations do not serve the needs of audiology practices, patients, and consumers. Licensed audiologists should be the primary drivers of legislation and legislative changes in their states when it comes to audiology assistants.

RECOMMENDED QUICK READ

Licensing of More Occupations Hurts the Economy, by Martin Kleiner, PhD, one of the foremost leading experts on occupational licensing and its impacts. Available at www.umn.edu. ■

References

- Academy of Doctors of Audiology (ADA). (2021). Audiology assistants and occupational licensure: The risks outweigh the benefits. ADA. Available from www.audiologist.org

- American Academy of Audiology (AAA). (2021). Position statement: Audiology assistants. AAA. Available at www.audiology.org

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Audiology assistants (Practice Portal). ASHA. www.asha.org/practice-portal/professional-issues/audiology-assistants/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). (2022). Board of directors meeting report. ASHA. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/reports/bod-meeting-report-january-2022.pdf

- Andrews, J., & Hamil, T. (2017). Audiology assistant scope of practice and utilization: Survey results. Audiology Today, 29(4), 48-55.

- Cavitt, K. (2018). 20Q: OTC hearing aids and a 21st-century pricing and delivery model - change is gonna come. AudiologyOnline, Article 23137. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Emanuel, D.C. (2022). 20Q: Occupational stress and audiologists. AudiologyOnline, Article 28159. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Karzon, R., Hunter, L., & Steuerwald, W. (2018). Audiology assistants: Results of a multicenter survey. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 29(5), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.17004

- Kingham, N. (2021). Audiology assistants: the key to efficiency in the audiology practice. AudiologyOnline, Article 27829. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Kleiner, M. (2017). The influence of occupational licensing and regulation. IZA World of Labor. doi: 10.15185/izawol.392

- Kleiner, M. (2018, January 23). Licensing of more occupations hurts the economy. University of Minnesota. https://www.hhh.umn.edu/news/professor-morris-kleiner-licensing-more-occupations-hurts-economy

- Larkin, M.A., Citron, D., & Cavitt, K. (2016). Highlights from AuDACITY 2016: Audiologist assistants - a good fit for your practice? AudiologyOnline, Recorded Course 28788. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Liebe, K. (2014, March 5). Opening Pandora’s box: A case for the enhanced audiology assistant. Hearing Health and Technology Matters. https://hearinghealthmatters.org/hearingviews/2014/pandoras-box-case-enhanced-audiology-assistant/

- National Conference of State Legislatures. (2017). The state of occupational licensing: research, state policies, and trends. https://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/HTML_LargeReports/occupationallicensing_final.htm

- Taylor, B. (2016). Interventional audiology: Broadening the scope of practice to meet the changing demands of the new consumer. Seminars in Hearing, 37(2), 120–136. doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1579705

- White House Report. (2015). Occupational licensing: A framework for policymakers. Available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/licensing_report_final_nonembargo.pdf

- Wince, J., Emanuel, D. C., Hendy, N., & Reed, N. (2022). Change resistance and clinical practice strategies in audiology. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, Advance online publication. doi.org/10.1055/a-1840-9737

Carolyn M. Smaka, Au.D., is editor in chief at Continued, an online continuing education company whose professional learning spaces include AudiologyOnline and SpeechPathology.com. She has worked in many clinical settings and in the hearing industry. Carolyn serves on ADA’s Advocacy committee, DEI committee, and is a past recipient of the Joel Wernick award.